Millets: The Future Smart Food

Deepak Kumar Patel1*, Shripati Dwivedi2 and Avinash Kumar2

April 25th 2025, 11:49:44 pm | 5 min read

Introduction

In the context of its National Food Security Mission, the Indian government is promoting millet. Discover how this food security-oriented cereal is climate-resilient. Millets have been the subject of several interactive activities held by the Government of India in commemoration of the 'International Year of the Millet'. These factors are expected to lead to continued millet production growth in India over the next few years. In order to increase the consumption of millet, it is necessary to promote its health benefits and sustainability as a crop to cultivate in an appropriate way. Furthermore, this will improve the welfare of farmers, food security, and nutrition.

With a 41% share of millet production in 2021, India is the largest producer, followed by Niger (12%) and China (8%). India also ranks 12th among countries with high millet yields. Our diet has long included millet. With low water and input requirements for production, they offer a number of health benefits as well as being environmentally friendly. A proposal presented by India and supported by 72 countries led the United Nations to declare the year 2023 as the ‘International Year of the Millet’, which was aimed at raising awareness and increasing the production and consumption of millets. The UN declared it on 5th March 2021 at the behest of the Indian government. Taking such care to honour humanity's traditional wisdom is essential. Food was first domesticated from these plants. An opening ceremony for the International Year of Millets (IYM) 2023 was held in Rome, Italy, by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations on 6th December 2022.

Background of Millets

Milum, the Latin word for grain, is the root of the word 'Millet'. It belongs to the family Poaceae, which is commonly known as the grass family. Over half a billion people across Asia and Africa depend on millets, which are grown in more than 130 countries. A group of small-seeded grains called millets has been cultivated around the world for thousands of years. Their high fibre content, vitamins, minerals, and proteins make them a great source of nutrition. Celiac disease sufferers or those with gluten sensitivities will benefit from their gluten-free properties. To make bread, cakes, and pasta, millets can be ground into flour and cooked whole as porridge. With low water and input requirements, millets also benefit the environment in addition to providing many health benefits. The Government of India (GoI) has prioritized millets because of their enormous potential to increase farmers' incomes and ensure food security worldwide. The year 2018 was declared the National Year of Millets, aiming to promote and generate greater demand for millets. In April 2018, millets were rebranded as "Nutri Cereals". Around 3500 BC, millets were cultivated on the Korean peninsula. Yajurveda texts mention millets in India. Until around 50 years ago, millet was extensively cultivated. India's traditional wisdom has been systematically neglected by the Western development model. The coarseness and primitive nature of millets are cited as reasons to avoid them. Rural people or ancestors were considered to be the only ones to consume it. In addition, millet production was negatively affected by the Green Revolution. It is estimated that millets made up 40% of all grain production before the Green Revolution. Twenty percent of the world's millet is produced in India, which produces 170 lakh tons a year. India's millets average 1,239 kg per hectare, compared to the global average of 1,229 kg. These Nutri cereals are annual, short duration (75 to 120 days) rainfed crops that grow well on shallow and low fertile soils with a pH range from acidic to alkaline soil. It has a low water requirement and can be grown even under extremely high temperatures and less rainfall. These are resistant to drought, resistant to most diseases and pests, and need minimum care.

Millets and Health

Compared to C3 plants, these C4 plants are more efficient at converting CO2 into carbohydrates. Besides being nutritional, millets are also climate resilient. The system ensures the security of people's food, nutrition, and economic well-being. Superfood millets are rich in macronutrients and micronutrients. In addition to being non-starchy polysaccharides, gluten-free proteins, high in soluble fibre, high in antioxidants, and low in glycemic index, they are also rich in bioactive compounds. It contains beta-carotene and vitamins B and C. As a low glycemic index grain, millets are ideal for diabetics since they contain non-starchy polysaccharides, fibre, and a low glycemic index. It improves gut health and reduces cholesterol levels because of its soluble fibre and millet protein. Those with celiac disease can benefit from millet, as they are gluten-free grains. Calcium is found in ragi, which is excellent for bone health, blood vessels, muscle contractions, and nerve function. The iron content of Kodo millet is high. Blood is purified, hypertension is reduced, and the immune system is regulated. Healthy neurons are maintained by foxtail millet. Little millet has beneficial effects on the thyroid. These cereals are called Nutri cereals because of their nutritional value. It is recommended to consume one millet a week on a rotational basis as part of your daily diet. Jowar is best eaten in summer, while Bajra is best eaten in winter. A good source of fiber, barnyard millet is often eaten during religious fasts. It is also beneficial for the health of the liver. The anti-cancer properties of browntop millet are well known. The following can be substituted for rice: Kutki, Sama, and Kagni. The grains need to be soaked at least six to eight hours before cooking because they are coarse. The regional level already provides millet khichdi and millet roti recipes. There are also many innovative recipes being developed professionally in hotels, bakeries, and in households, including millet dosa, millet idli, pancakes, millet bread, waffles, crispy crumbs in salads, and cookies. Ending hidden hunger and fulfilling the goal of zero hunger will be possible with new ideas to make it more pleasant and more acceptable to all age groups. Sustainable agriculture can be achieved with millet farming, and farmers can prosper.

Nutritional Information of Millets

Composition of different millets (for 100 g)

| Millets | Carbohydrates (g) | Protein (g) | Fat (g) | Fibre (g) | Minerals (g) |

| Pearl millet | 67.0 | 10.6 | 4.8 | 1.3 | 2.3 |

| Finger millet | 72.05 | 7.3 | 1.3 | 3.6 | 2.7 |

| Foxtail millet | 63.2 | 12.3 | 4.0 | 8 | 3.3 |

| Proso millet | 70.4 | 12.5 | 3.1 | 2.2 | 1.9 |

| Kodo millet | 66.6 | 8.3 | 3.6 | 9 | 2.6 |

| Little millet | 65.55 | 7.7 | 2.55 | 7.6 | 1.5 |

| Barnyard millet | 68.8 | 11.2 | 3.6 | 10.1 | 4.4 |

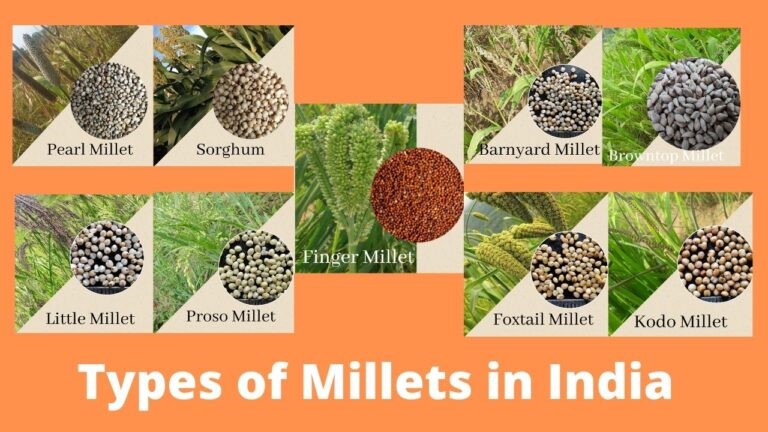

Types of Millets in India

Among the millets common to India are Jowar (sorghum), Bajra (pearl millet), ragi (finger millet), Jhangora/Sanwa (barnyard millet), Barri (Proso or common millet), Kangni (foxtail/ Italian millet), Kodra (Kodo millet), among others. We will also learn their regional names as we read about them in detail.

1. Barnyard millet is a good source of iron and fibre. In Tamil, it is called Kuthiravali, in Kannada Oodhalu, in Telugu Odalu, in Malayalam, it is called Kavadapullu, and in Hindi, it is called Sanwa.

2. Finger Millet is an excellent substitute for oats and cereals. In Kannada, Ragi is called Ragulu, Kelvaragu is called Kelvaragu, and Koovarugu is called Koovarugu in Malayalam and Mundua is called Mundu.

3. Foxtail Millet is highly nutritious in minerals and vitamins. Tamil calls it Thinai, Telugu calls it Kirra, Malayalam calls it Thinna, Kannada calls it Navane, and Hindi calls it Kangni.

4. Little Millet is also enriched with iron and fibre. Malayalam's Chama, Kannada's Same, Tamil's Samai, Telugu's Sama and Hindi's Kutki are the regional names.

5. Proso Millet has many names in India, including Barri in Hindi, Panivaragu in Tamil and Malayalam, Baragu in Kannada, and Varigalu in Telugu.

6. Pearl Millet is one of the best sources of protein, it is known in Hindi as Bajra, Kannada as Sajje, Telugu as Sajjalu, Tamil as Kambu, and Malayalam as Kambam.

Importance of Millets

It has been estimated that between 2016 and 2017, the area under millet cultivation decreased by 60% (to 14.72 million hectares) as a result of changes in consumption patterns, the conversion of irrigated areas to wheat and rice cultivation, the absence of millets, low yields, dietary habits, and decreased demand. As a result, women and children became malnourished due to a decline in vitamins, proteins, iron, and iodine.

According to the Global Hunger Index - GHI, India ranks 107 out of 121 countries. Despite being the second worst in the world when it comes to child malnutrition, our country remains in the plight of the poor. In spite of nearly five decades of Public Distribution System and Targeted Public Distribution System operation, this scenario persists. Because millets have long been overlooked, only wheat and rice have been distributed.

Despite their importance from the point of food security at the regional and household levels, millets have a relatively lower position among the food crops in Indian agriculture. Keeping this in mind, here are some points highlighting millets' importance.

1. There are many types of millet that are non-acid forming and non-glutinous, highly nutritious, and easy to digest. As low glycemic index (GI) foods are gluten-free, they help slow down the release of glucose over a longer period of time, reducing diabetes risk. A variety of millets can be incorporated into the diets of celiac disease patients.

2. There are many minerals present in millets, including calcium, iron, zinc, phosphorus, magnesium, and potassium. Furthermore, it contains dietary fibre, vitamin B6, beta carotene, and niacin in significant amounts. In addition to strengthening the nervous system, lecithin is available in high amounts. It is, therefore, possible to overcome malnutrition through regular consumption of millets.

3. The anti-nutritional factors in millets can be reduced by certain processing procedures, despite their contents of phytochemicals such as tannins, phytosterols, polyphenols, and antioxidants.

4. Due to their wide range of tolerance, millets can grow from coastal areas of Andhra Pradesh to moderate altitudes of North-eastern states and hilly regions of Uttarakhand. There is a wide range of conditions in which millets can thrive, including variations in moisture, temperature, and soil type, including heavy to sandy infertile soils.

Advantages of Millet Production

In spite of their coarse appearance, millets are now referred to as nutria-millets or nutria-cereals because of their nutritional benefits. There are several advantages to producing millets in India.

1. Due to their drought resistance and ability to grow under harsh conditions, millets are called 'miracle grains' or 'crops of the future'.

2. Millets serve two purposes. Farmers cultivate it both as food and fodder, maintaining food/livelihood security for millions of households.

3. As millets reduce atmospheric carbon dioxide pressure, they contribute to mitigating climate change. Wheat, a thermally sensitive crop, along with paddy, contributes greatly to climate change by releasing methane into the atmosphere.

4. There is no need to use chemical fertilizers to produce millets. Crops grown from millet do not attract pests or are affected by storage.

5. The nutritional value of millets is remarkable, whether it is vitamins, minerals, fibre, or other nutrients. In comparison with wheat and rice, it is nearly three or five times more nutritious. The polyphenols, antioxidants, and cholesterol-lowering waxes found in sorghum (Jowar) make it an important source of health benefits.

6. With their high dietary fibre content coupled with a low glycaemic index, millet helps curb obesity, reduce CVDs, diabetes, and cancers and lower the risk of hypertension.

Conclusion

There is also a strong focus on millet in the G-20 meetings, and delegates will have the opportunity to experience millet through tastings, meetings with farmers, and interactive sessions with start-ups and FPOs on the day of the meetings. There is a true spirit of working together that can be seen in the celebration of the International Year of Millets 2023, as part of the government's whole government approach. As a result, it is extremely important that we increase the production of these crops and revert the control of production, distribution and consumption to the people at the same time, so as to ensure food and nutrition security for our country.

References:

Renganathan, V. G., Vanniarajan, C., Karthikeyan, A., & Ramalingam, J. (2020). Barnyard millet for food and nutritional security: current status and future research direction. Frontiers in genetics, 11, 500.

Gupta, S. M., Arora, S., Mirza, N., Pande, A., Lata, C., Puranik, S., ... & Kumar, A. (2017). Finger millet: a “certain” crop for an “uncertain” future and a solution to food insecurity and hidden hunger under stressful environments. Frontiers in plant science, 8, 643.

Sood, S., Khulbe, R. K., Gupta, A. K., Agrawal, P. K., Upadhyaya, H. D., & Bhatt, J. C. (2015). Barnyard millet–a potential food and feed crop of future. Plant Breeding, 134(2), 135-147.

Jhan, F., Gani, A., Noor, N., Malla, B. A., & Ashwar, B. A. (2022). Nano reduction coupled with encapsulation as a novel technique for utilising millet proteins as future foods. Ultrasonics Sonochemistry, 86, 106006.

Saxena, R., Vanga, S. K., Wang, J., Orsat, V., & Raghavan, V. (2018). Millets for food security in the context of climate change: A review. Sustainability, 10(7), 2228.

Muthamilarasan, M., & Prasad, M. (2021). Small millets for enduring food security amidst pandemics. Trends in Plant Science, 26(1), 33-40.

Lokesh, K., Dudhagara, C. R., Mahera, A. B., & Kumar, S. (2022). Millets: The future smart food.

Sachdev, N., Goomer, S., & Singh, L. R. (2021). Foxtail millet: a potential crop to meet future demand scenario for alternative sustainable protein. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 101(3), 831-842.

Bora, P., Ragaee, S., & Marcone, M. (2019). Characterisation of several types of millets as functional food ingredients. International journal of food sciences and nutrition, 70(6), 714-724.

Kumar, A., Tomer, V., Kaur, A., Kumar, V., & Gupta, K. (2018). Millets: a solution to agrarian and nutritional challenges. Agriculture & food security, 7(1), 1-15.

Kumar, A., Metwal, M., Kaur, S., Gupta, A. K., Puranik, S., Singh, S., ... & Yadav, R. (2016). Nutraceutical value of finger millet [Eleusine coracana (L.) Gaertn.], and their improvement using omics approaches. Frontiers in plant science, 7, 934.

Kaimal, A. M., Mujumdar, A. S., & Thorat, B. N. (2021). Resistant starch from millets: recent developments and applications in food industries. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 111, 563-580.

Saleh, A. S., Zhang, Q., Chen, J., & Shen, Q. (2013). Millet grains: nutritional quality, processing, and potential health benefits. Comprehensive reviews in food science and food safety, 12(3), 281-295.

Thapliyal, V., & Singh, K. (2015). Finger millet: potential millet for food security and power house of nutrients. International or Research in Agriculture and Forestry, 2(2).

Das, S., Khound, R., Santra, M., & Santra, D. K. (2019). Beyond bird feed: Proso millet for human health and environment. Agriculture, 9(3), 64.

Taylor, J. R., Schober, T. J., & Bean, S. R. (2006). Novel food and non-food uses for sorghum and millets. Journal of cereal science, 44(3), 252-271.

Gowri, M. U., & Shivakumar, K. M. (2020). Millet scenario in India. Economic Affairs, 65(3), 363-370.

Sharma, A., Sood, S., & Khulbe, R. K. (2013). Millets-food for the future. Biotech Today, 3(1), 52-56.

Kumar, K. A. (1989). Pearl millet: current status and future potential. Outlook on Agriculture, 18(2), 46-53.