The Doomsday Vault (Svalbard Global Seed Vault): The worldwide biodiversity backup plan

Swathy, V.1* and Niji, M.S.2

September 18th 2025, 8:44:19 am | 5 min read

Introduction

In this era of increasing threat to biodiversity, the concept of conservation tops the list of goals for agriculturalists as well as ecologists. Climate change and world food security are the two factors that requires immediate attention. Plant genetic resources form one of the most valued assets of nature’s biodiversity. It includes plants that we use today for cultivation, those that were in cultivation years back, and those that are still wild in nature. The plants that we cultivate today are the results of years of breeding and domestication efforts. But with the advance of time, as more global economies became uniform resulting in narrowed production environments, our dependence on these resources has also narrowed. This has led to the narrowed genetic base for plant biodiversity. Scientific reports say that today 75% of world food is generated from 12 plant species and 5 animal species (Sarala Yadav et al., 2016). This indicates that even a small but sudden climate change or a new disease or pest or environmental calamity can have a large-scale impact on food security anywhere around the world.

Conservation may be carried out either in the natural habitat of the plant (in-situ conservation), such as biosphere reserves, or away from the habitat (ex-situ conservation). Gene banks form examples of ex-situ conservation and represent our efforts for preventing biodiversity loss. Seed banks may be considered as a type of gene bank, as it carries out the same function as that of a gene bank, the storage material being seeded.

Plants whose seeds are susceptible to faster loss of viability (Recalcitrant seeds), cannot be stored as seeds, hence they are stored as tissue-cultured propagules (In vitro gene bank), in the form of DNA (DNA banks) or cryopreserved in liquid nitrogen at -196°C (Cryo bank). Orthodox seeds can be dried and stored for decades without loss of viability and hence are conserved in seed banks. Such seeds are stored under specified conditions and their germination rates are monitored at regular intervals at the seed banks. When suspected to have their germination rate fallen below a critical level, they are brought to life by sowing in suitable soils. Fresh seeds are harvested from the plants and the process of long-term storage is repeated, only to be regenerated decades later. However, seed banks themselves are at threat under certain circumstances, which has led to the concept of developing a backup for seed banks – “the backup of the backups”. Thus in 2008, this idea was executed by the Norway Government along with the help of certain international funding agencies, thereby giving rising to the Svalbard Global Seed Vault (SGSV) or the Doomsday Vault.

WHY IS A GLOBAL SEED VAULT REQUIRED?

Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) and other supporting bodies appreciated the idea of a global seed vault due to reasons perceived and explained by Cary Fowler, the American agriculturalist and the former executive director of the Global Crop Diversity Trust currently serving as a Senior Advisor to the trust.

The main reasons are:

i. To avoid loss of biodiversity due to unexpected malfunctioning of equipment at gene banks

ii. Natural disasters may result in complete loss of accessions at gene banks as well as affect the farming sector of the country. Hence to re-establish the vegetation, seeds of all crops adapted to that region are required. This is possible only if a backup has been made earlier.

iii. The lack of funding at gene banks for conservation has resulted in their languishment and deterioration of resources

iv. Civil strikes within countries and wars between countries pose a great threat to both in-situ and ex-situ conservation units.

SVALBARD GLOBAL SEED VAULT:

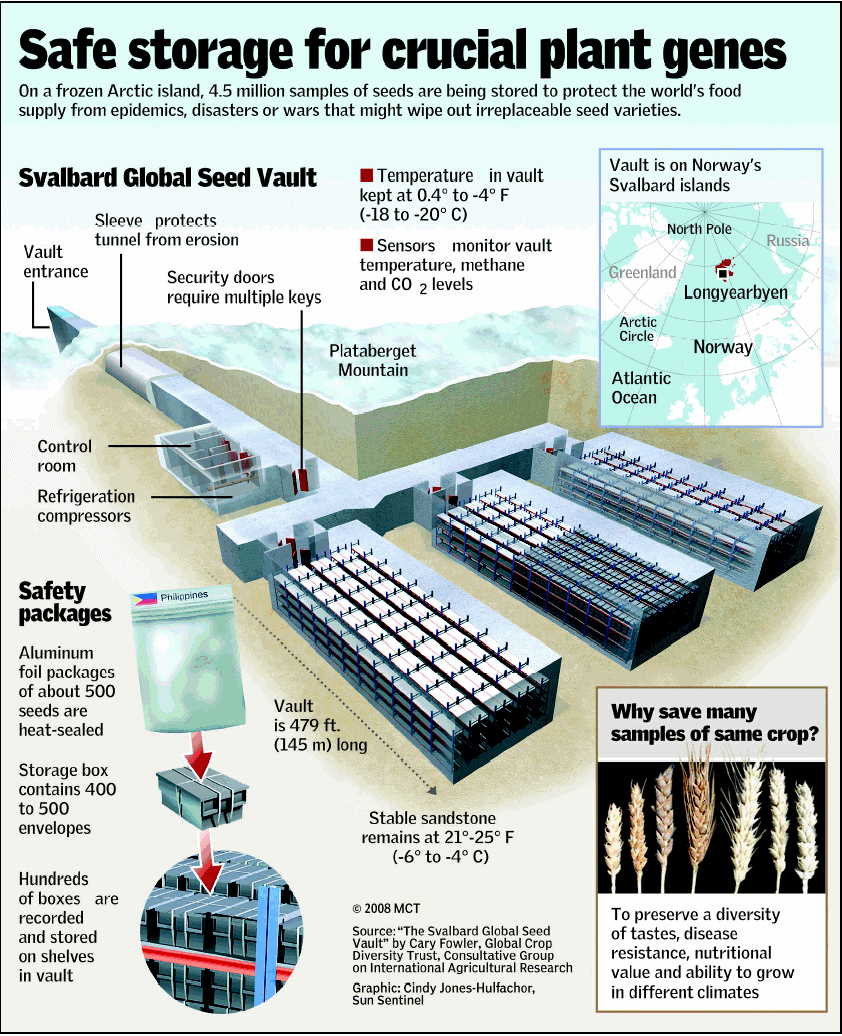

The Svalbard Global Seed Vault is a safe seed bank on the Norwegian island of Spitsbergen, near Longyearbyen, nearly 1000 km from the North pole. It is about 130 m above sea level and has an underground facility blasted out of permafrost (a thick layer of subsurface soil with a temperature below 0°C). It is also called Noah’s Ark for seeds considering its function of saving the earth’s left-over biodiversity.

Fig 3: Location of Global Seed Vault

The history of this seed vault dates to the 1980s when the Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) and the International Board of Plant Genetic Resources (IBPGR) together brought up the concept of the global central seed bank. In 1989, IBPGR started surveying relevant sites in Svalbard. However, until 2004 there were no agreements regarding the idea when FAO’s International Treaty for Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture was accepted. This treaty served as the basis for the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Ministry of Agriculture and Food to start with the execution of the idea after having received a positive response from FAO’s Commission for Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture. Thus by 2007, the vault was constructed by Norway and FAO along with IBPGR which took care of administrative operating costs. The vault was officially opened on 26th February 2008.

The vault has been built as a tunnel 100 m long dug into a mountain. The entrance portal is the only visible part of the vault. The tunnel leads into three chambers where seeds are stored on metal racks under specified conditions of temperature and humidity to maintain the viability of seeds. Atmosphere conditions within chambers are maintained at -18°C with help of machinery powered by electricity from the local power station. The most attractive feature of this vault is that a temporary temperature backup of 3-5°C will be ensured by the natural permafrost even in case of unexpected technical failure. The mountain is secured with bolts and sprays concrete while the interior floor is made of asphalt (Sarala Yadav et al., 2016). It has a total storage capacity of 4.5 million seed samples with each chamber having a capacity of nearly 1.5 million samples. Gene banks all around the world can deposit their samples here.

Fig 4: Svalbard Global Seed Vault

Feature Highlights:

Black box arrangement – This implies that the sample will be stored in sealed envelopes at the vault and that the seeds deposited by the depositor gene bank can alone access the seeds but only in case when the sample has been lost completely from the concerned gene bank. Also, the vault would not be responsible for monitoring the sample viability.

Cost-free deposition of samples – The vault provides a facility for storage free of cost on request from private and public depositors.

Packaging and shipment – The depositors are expected to bear the costs of packaging and shipment of seeds from the vault and to the vault for deposition.

Replacement of old seed stocks – The vault is not expected to monitor the vitality of samples. Hence the concerned gene bank has to monitor and replace the old stock of samples as and when their germination rate falls. However, it will accept the new shipment when the stored samples have lost fertility.

Fig 5: Highlights of Svalbard Global Seed Vault

Fig 6: Inside the Global Seed Vault

WHY SVALBARD?

Svalbard is considered the appropriate site for the vault because:

1. The permafrost offers a natural freezing temperature for storing the seed samples excluding chances of biodiversity loss due to equipment failure. Also being at a higher altitude from sea level, it is believed to be away from the threat of melting polar glaciers

2. It serves as a site with a unique combination of remoteness and accessibility.

3. Military activity is prohibited at this location under the terms of the Svalbard foundation.

4. The mountainous location provides security and is geologically stable with low radiations.

5. The location is also politically sound.

CURRENT STATUS OF VAULT:

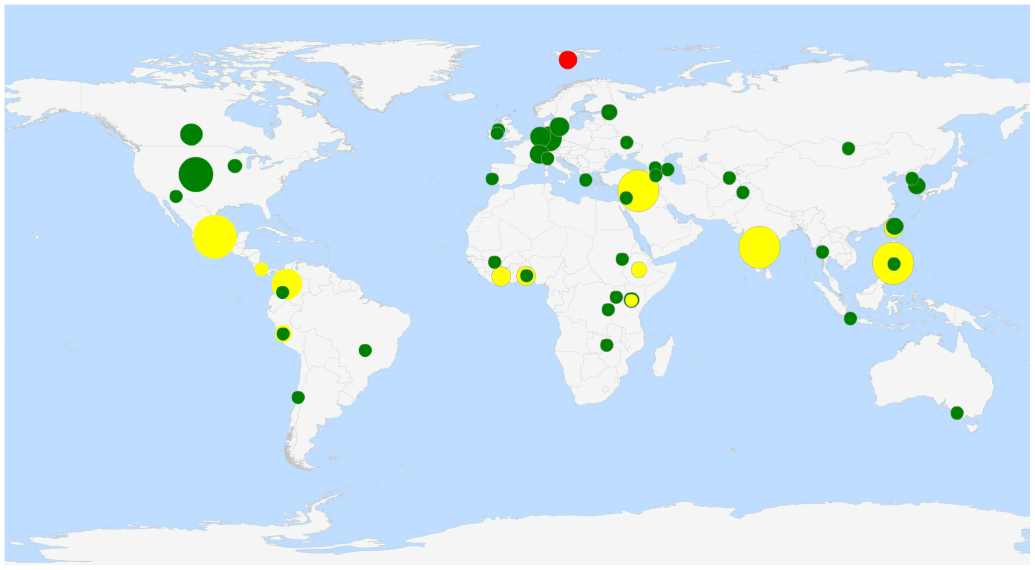

Fifteen years of saving world biodiversity, the vault has in store nearly 1.5 million seed samples of about 5000 different plant species collected from nearly 170 gene banks across the world. The largest depositors among national gene banks are the United States, Germany, Canada, Australia, The Netherlands, South Korea, and Switzerland. Recent news about the vault reports that it has nearly 3000 varieties of coconut, 4500 varieties of potatoes, 35000 varieties of maize, 125000 varieties of wheat, and 200000 varieties of rice. As of February 2020, 60,000 more seed samples were deposited in the vault from 36 different institutions across the world. In October 2021, the Crop Trust authorities announced addition of 22 more species into the storage facility at the vault.

Fig 7: Status of the Global Seed Vault

(Source: Svalbard Global Seed Vault, Credit: Accurate- Giovanni Magni, Stefania Guerra, Antonella Autuori and Luca Mattiazzi)

CONCLUSION AND FUTURE PROSPECTUS:

Svalbard Global Seed Vault has so far proved to be a global insurance policy against biodiversity deterioration. It serves to hold onto the earth’s left-over biodiversity which is essential for the future sustenance of agriculture and thereby humankind. It has helped several gene banks to protect their resources from equipment failure. Natural as well as accidental disasters can no longer completely wipe out the plant diversity of at least some regions around the world. The seed vault at Aleppo carrying nearly 1,35,000 samples of plant varieties that are almost extinct now, remains inaccessible even today after the war in Syria. This one incident alone proclaims the need for SGSV. The gene banks that are on the verge of impairment due to a lack of funding can have their resources saved at SGVS. Thus, together with SGSV, we can safeguard distinct varieties, landraces, crop wild relatives as well as cultivated varieties for future plant breeding.

Fig 8: National and International gene banks with safe deposits at SGSV (Ola T Westengen et al., 2013)

However, some of the commonly raised anxieties about the vault include its security which remains untested. Recent reports state that during the melting period, there have been problems with water leakage in the tunnel (Asmund Asdal and Luigi Guarino, 2018). This has increased the concern about the vault’s ability to withstand climate change although Svalbard is still believed to be the ideal place for holding global backup. To avoid such worries, the authorities must ensure as well as explain the stability aspects of building the vault to the member countries. Apart from this, the deposition of seeds away from farmers and communities who originally created them is suspected to be against the idea of IPR (Intellectual Property Rights). To access seeds, farmers and associated communities must integrate themselves into a whole new institutional framework, about which they are totally unaware. This in turn has created a wave of disagreement among them. This should be avoided by amending the laws governing deposition and patent-related issues regarding SGSV. It has also been discussed by scientists around the world that SGVS promote sole reliance on one conservation strategy- the ex-situ method. Hence ideas pertaining to the conservation of habitat are welcomed more nowadays.

With all the hikes and lows, Svalbard Global Seed Vault to date claims the title of “Doomsday Vault”, saving seeds for the future, and has succeeded to be the best in its niche. Whether at habitat or away from the native place, this vault is proof of what can be accomplished when nations work hand-in-hand for a better tomorrow.

REFERENCES

Asdal, A. & Guarino, L. (2018). The Svalbard Global Seed Vault -10 Years – 1 million samples: 16(5), 391–392.

Fowler, C. (2008a). Faults in the vault Not everyone is celebrating Svalbard, (February), 1–3.

Fowler, C. (2008b). The Svalbard Seed Vault and Crop Security.

Westengen, O. T., Jeppson, S., & Guarino, L. (2013). Global Ex-Situ Crop Diversity Conservation and the Svalbard Global Seed Vault: Assessing the Current Status, 8(5).

Yadav, S., Yadav, S. K., & Kumar, M. (2016). Svalbard Global Seed Vault: Global central seed bank, 31–38.